This essay was originally published by Classical Wisdom after winning their Stoic Essay Writing Contest in 2022. You can read the original post here.

What happens to each of us is ordered. It furthers our destiny.

Marcus Aurelius[1]

We never know when our lives might be changed suddenly and irrevocably. 2015 was one of the most successful years of my career as a multidisciplinary artist and vocal coach. I was teaching privately and at our local university and collaborating with several other performing artists. My largest project was writing and performing libretto and music for an upcoming dance opera. After a three week intensive with the dance opera company, my collaborator came down with a virus. I gently hugged her aching body and said goodbye. The next day I was sick. I still haven’t recovered.

Stoicism has been of great help in managing my mental and physical health while living with chronic illness. I also believe Stoicism has the potential to shift how society views those disabled by chronic illness—from burdens to human beings capable of flourishing—and to offer the support necessary to make that happen.

My story of becoming sick with a virus and not recovering is becoming more common as the aftereffects of the COVID pandemic sweep the world. Numerous people who were sick with a mild version of COVID are still sick with “long COVID”, experiencing similar symptoms to what I was diagnosed with: Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). 56% of Canadians with COVID report symptoms long after infection.[2] 962,000 people in the UK are still unwell.[3] Most of them, like I, are too sick to work, and have no approved treatments.

My initial symptoms were tingling all over my body and overwhelming fatigue. Not the fatigue from pulling an all-nighter, but where going from couch to bathroom wears you out for hours. Where chewing is so exhausting you subsist on liquid meals. Where conversing, reading, or writing sets your brain into a deep fog. Where you shave your head because showering is too exhausting. That sort of fatigue.

About two months into this ordeal, my doctor brought up the possibility of ME/CFS. Until we ruled out other causes I was to rest and not exert myself in any way. After three months, I told my collaborators and voice students I was too sick to work.

ME/CFS has abysmal research funding and the diagnostic criteria isn’t taught in medical schools. Current treatments are limited and only work for some. Up to 60% of ME/CFS (and likely long COVID) patients are women[4] and many aren’t believed when they describe their symptoms because all their tests, like mine, come back normal. People with moderate ME/CFS—like myself—function at about 50% of their previous capacity if they pace themselves well. People with severe ME/CFS are bedridden, live in darkness and silence because of severe sensory sensitivities, and some must be fed through J-tubes directly into their digestive systems.

You mustn’t forget that this body isn’t truly your own, but is nothing more than cleverly molded clay.

Epictetus[5]

In illness everything is laid bare. We suddenly understand just how much we take our bodies for granted. Our ability to work, breathe, walk, write, listen is ripped away. We are an ill thing burdened with aches, pains, and other symptoms. Sometimes the symptoms are so intense we cannot do anything but experience them. Like the box of pain in Dune,[6] we are forced into an initiation that breaks us down into our discrete parts. We drown in sensation.

How Illness Became My Way

You have to assemble your life yourself —action by action. And be satisfied if each one achieves its goal, as far as it can. No one can keep that from happening.

Marcus Aurelius[7]

What does a composer who can’t listen to music do? A performer who can barely stand or speak? A writer who can barely read? I lost my income and my ability to create art. I knew if I did not manage to find some way to create I would fall into a deep depression on top of being so physically ill.

I don’t remember what triggered a need to read more Stoicism, but I got a copy of Ryan Holiday’s The Daily Stoic and found the short entries concise enough for my fatigued brain to handle. Each day I read a page and wrote down one line. There were hours in the day I needed to remain absolutely still and so I contemplated—not ruminated, contemplated—on how I might use Stoicism to help manage my mind since my body was utterly outside my control.

The impediment to action advances action.

What stands in the way becomes the way.

Marcus Aurelius[8]

Since I could hardly move, I needed to embrace a slow and sedentary creative medium. Writing wasn’t possible since brain fog and aphasia (trouble finding words) were major issues. I saw a period drama in which a woman was told to “take to her bed to work on her embroidery.” I had taken to my bed. I had done some Ukrainian cross stitch in the past. I had created some text/image pieces before I got sick. I slowly gathered embroidery supplies and started stitching.

I continued contemplating Stoic maxims throughout the day and now had an activity to do while resting. I began to love my life again. My illness gave me the gift of time—something all artists desire—and my brain could rest in the slow, deliberate art of hand embroidery.

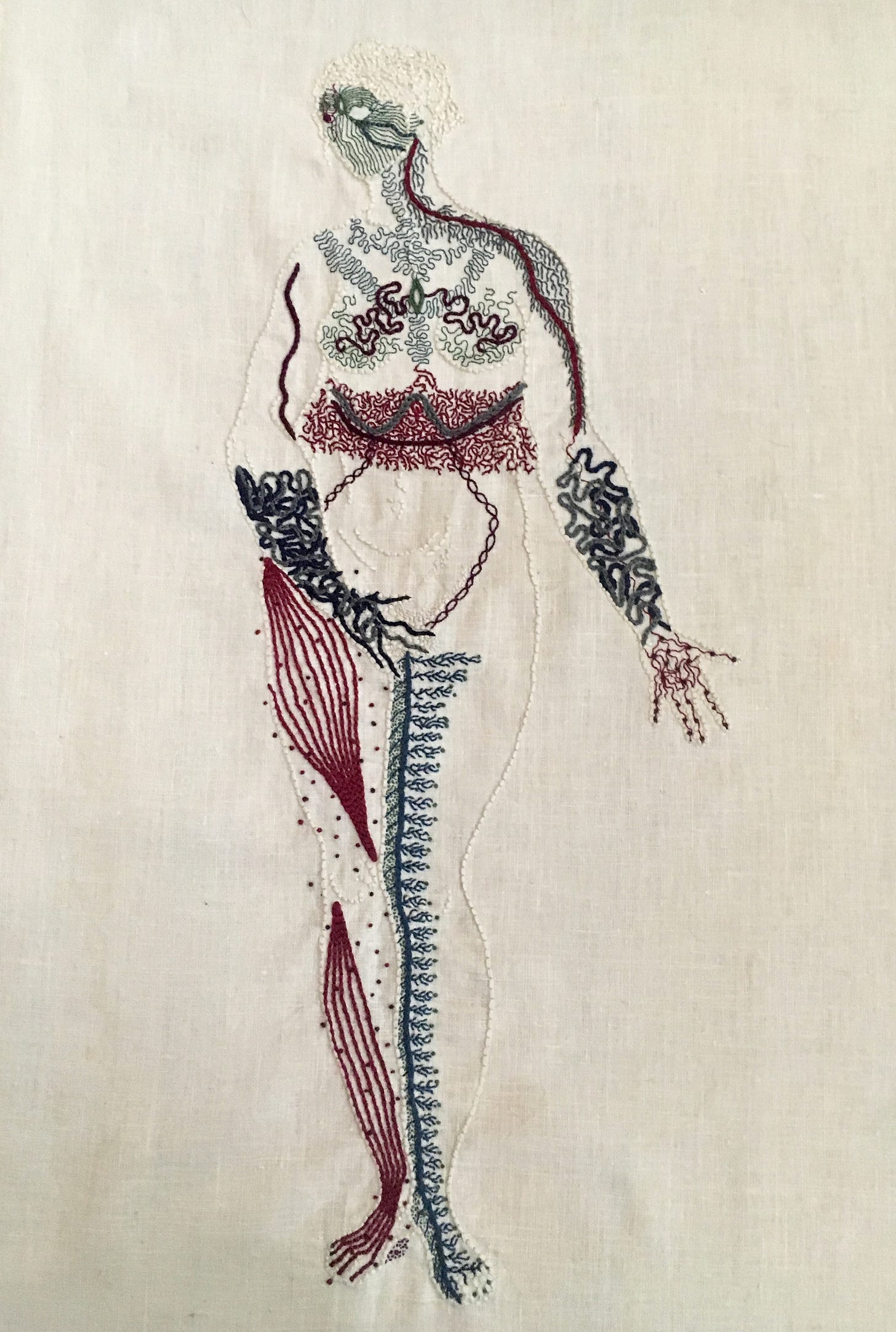

A deepening of the concept of ‘the obstacle is the way’ and of the practice of embroidery happened a couple months after I started stitching: as I meditated—my nervous system pinging, tingling, and sparking viscerally through me—I focused in on those sensations. I made them my meditation. As I honed in, I saw each discrete sensation as designs, colours, and stitches. After this experience, I began to stitch my neurological sensations as I experienced them.[9] Because of this exquisite attention, the symptoms became my creative practice—the obstacle became the way in an even deeper way, and so began my symptomatology series. I found I loved my fate, my days, my new creative practice. I felt the power of Amor Fati.

Virtues as Supports

ME/CFS is a disease with few options for treatment and few doctors who understand it. Many patients fall into depression and some commit suicide. Our society sees illness as amoral—blaming the ill for their sickness instead of seeing health as a preferred indifferent.[10] To blame someone for catching a virus is illogical at best, and ableist at worst. The four Stoic Virtues offer principles through which we can make positive changes both as a society and as chronically ill individuals.

We live in a capitalist society where the worth of a person is wrapped up in their ability to work and/or make money. When one is ill—especially with fatigue—such work is near impossible. We cannot contribute to capitalist society and are seen as burdens. This—paired with abysmal social supports for disabled people—causes extreme wealth inequality. It is expensive to be disabled. We require help with basic necessities like shopping, cooking, cleaning, and sometimes washing ourselves. We require mobility aids. Capitalism is a punitive system for the disabled and chronically ill.

The virtue of Justice is what ME/CFS and long COVID requires. Justice asks: With so many people becoming too disabled to work, what are the options for them? What could healthy people and society do to better support this ever-growing section of the population?

Even if/when we are able to recuse ourselves psychologically from the idea that work = worth, we are left with the cultural pressure to do more than our bodies are capable of. This is where the virtue of Moderation or Temperance comes into play.

If you seek tranquility, do less.

Marcus Aurelius[11]

One of the best ways to manage fatigue is through pacing ourselves. If those of us with ME/CFS exceed our limits, we fall into post-exertional malaise (PEM)—flu-like symptoms—for days to months depending how far we have pushed ourselves. People have gone from mild ME/CFS to bedridden after following the advice of ignorant doctors who recommend exercise.

Learning to love doing less—to be temperate by creating routines with ample rest and recovery time—means we can flourish as individuals. We can create meaning and self-worth in ways that honour and accommodate the needs of our bodies. I did this through embroidery, and contemplation on the virtue of Moderation can help others find ways that work for them.

To use the discretion of Moderation without falling into laziness requires Wisdom. To turn philosophy into a life well lived in the midst of debilitating symptoms requires Wisdom. Wisdom is key.

Anathema to Wisdom is hubris, and I would be remiss not to mention a major issue facing those with ME/CFS and long COVID: disbelief. There is a cohort of psychiatrists who believe—despite biomedical proof to the contrary—that these illnesses are purely psychiatric.[12] Some doctors have put severely ill people with ME/CFS into psychiatric institutions. Through advocacy work, psychiatric interventions and exercise are no longer listed as treatments for ME/CFS by the CDC, but doctors still recommend them. Funding must be channeled into biomedical research towards viable treatments for these illnesses.

It takes Courage to delve into medical papers to gain information necessary to advocate knowledgeably for oneself. It takes courage to challenge a psychiatric misdiagnosis that overshadows your very physical symptoms. Being adversarial towards—fighting against—our illness doesn’t serve us. Acceptance and seeing where we have agency does.

Eudaimonia (Flourishing)

My life is now calm, ordered, and balanced. The exquisite attention I offer in my symptomatology embroideries is a way of dissecting, understanding, and being compassionate about my symptoms. I am overjoyed and grateful I am significantly less symptomatic since the onset of ME/CFS in 2015, but I am also aware how the many self-compassionate and temperate changes I’ve made in my life due to my Stoic practices help me listen deeply to my body’s needs.

Surviving a major illness changes people. The Stoic virtues of Justice, Moderation, Wisdom, and Courage tied together with the concept and practice of Amor Fati have helped me flourish within my limitations, even though an outside observer may not have that impression. I now reach for these practices when overwhelmed by symptoms, medical appointments, and demands on my limited energy.

Stoicism gives us a way through life’s most challenging situations, and has the potential to shift unhelpful views about chronic illness and disability on a much larger scale. We need more witnessing of this truth. Stoicism gives us the tools to do so.

[1] Marcus Aurelius, Meditations. trans. Hays, Gregory. Modern Library, 2003. Book V, section 8, page 56.

[2]Statement from the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada on July 7, 2021

[3] Marshall, Michael. The four most urgent questions about long COVID. Nature. June 9, 2021. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01511-z?utm_source=twt_nat&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=nature

[4] Valdez, Hancock, et al. Estimating Prevalence, Demographics, and Costs of ME/CFS Using Large Scale Medical Claims Data and Machine Learning. Frontiers in Pediatrics. Jan 8, 2019.

[5] Epictetus, Discourses, Fragments, Handbook. Trans. Hard, Robin. Oxford World’s Classics, 2014. Discourses Book I, Chapter 1, verse 11, page 5.

[6] In Frank Herbert’s science fiction novel, Dune, the main character, Paul Atreides, is put through an initiation where he must place his hand in a box that causes extreme pain. If he removes his hand from the box, he will be killed instantly by a Bene Gesserit priestess holding a “Gom Jabbar,” a needle tipped with cyanide.

[7] Meditations. VIII, 32, pg 107. Trans. Hays

[8] Meditations, V, 20, pg 60. Trans. Hays

[9] The image in this paragraph is Body Map (2016). Embroidered cotton thread on linen by Lia Pas.

[10] The Stoic indifferents—things we have no control over—include health, wealth, property, and social standing.

[11] Meditations IV, 24, pg 42. Trans. Hays

[12] The most infamous case of this is Michael Sharpe’s now disproven PACE Trial results. Entry on Michael Sharpe and the PACE trial on MEAction’s Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Encyclopedia. https://me-pedia.org/wiki/Michael_Sharpe